Secret Stories Behind The Greatest Classical Compositions: Bach's Brandenburg Concerto

Johan Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos are classical music standouts for numerous reasons. This collection of six concertos nearly fell victim to becoming lost history, as have so many of Bach’s works. Yet today they’re considered the virtuoso collection of the variety and apex of Baroque music.

Each concerto is a concerto grosso, a concerto that’s a continuous interplay of small groups of soloists and full orchestra. Bach, himself, titled the compilation of concertos simply “Concerts avec plusieurs instruments” (concerts for several instruments). Indeed, the range of instruments with solos throughout the six concertos was designed to give opportunities to show the potential of nearly every instrument in the orchestra. Even the recorder got a solo. The recorder.

Each concerto itself presents a different example of Baroque music, sort of a Baroque musical travelogue moving through “the courtly elegance of the French suite, the exuberance of the Italian solo concerto and the gravity of German counterpoint.”

It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact dates when each concerto was written, as early incarnations and versions of each concerto can be found before Bach completed and compiled the final versions known today as the Brandenburg Concertos. Generally, it’s believed Bach may have begun composing some of the works that made it into the final version as early as 1708. What’s undisputed is that they were completed in 1721. How do we know? Because, like pretty much everyone throughout history, Bach needed a job.

The concertos as job application

One of the explanations that the concertos provide such breadth and depth of musical variety is because Bach compiled them as a job application to Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt, younger brother of the King. As such, it’s one of the few manuscripts that Bach wrote out himself, rather than give to a copyist. He also included an introduction and dedication to the Margrave requesting that he be given employment. At the time, Bach was the Kapellmeister in the small town of Cöthen. Working for His Royal Highness would have been a seriously upward move.

Alas, Bach didn’t get the job. He didn’t even get a reply. It’s believed that the Margrave never had the works performed, employing only a small orchestra considered to have only middling talent. Thus, it’s believed that had the Margrave even taken a look at Bach’s lovely leather-bound manuscript, he wouldn’t have had the means of having the concertos performed.

The concertos lost and found

The Margrave’s apparent disinterest in the concertos risked having them lost entirely, but kept them sufficiently preserved so that when they were eventually rediscovered – the manuscript was in great shape.

The Margrave died in 1734, at which time the manuscript was sold for roughly the equivalent of $24. Eventually, it ended up being found by the custodian of the Prussian royal library in 1849. The concertos were then published, for the first time, in 1850. They were given the name the “Brandenburg Concertos” in 1873, by Phillip Spitta in his biography of Bach.

The rare manuscript was almost lost again during World War II before another librarian stepped in to save the day. Due to heavy bombing and fighting in Germany, a librarian transported the manuscript out of the country. Unfortunately, his train fell under an aerial bombing as well. The librarian escaped into the forest with the work under his coat. It’s now safely housed in the Berlin State Library.

The performances

Due to the concertos inauspicious beginnings, it’s unclear exactly when they were first performed. While it’s widely believed the Margrave’s court orchestra never performed them, it’s also widely believed that Bach’s provincial orchestral did.

The King of Prussia at the time wasn’t a great fan of the arts. When he ascended the throne shortly before Bach took his position as Kapellmeister in Cöthen, he disbanded the royal court orchestra in Berlin. The result was that a lot of wonderfully talented musicians needed work. Many of them found their way to Cöthen, as the town’s local royal patron, Prince Leopold, was a music fan. Thus Bach was able to compose for a good number of skilled musicians who could perform what he was writing.

In truth, we don’t know when the first performance of the Brandenburg Concertos took place. Some of the earliest known recordings of performances date to the 1920s, including performances at the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra recorded in 1923 and the Berlin State Opera Orchestra recorded in 1925.

However, their entry into popular consciousness is attributed to German violinist Adolph Busch. Busch left his homeland in the early 1930s, denouncing the fascist Nazi regime. Eventually making his way to the United States, he put together the Busch Chamber Players to promote what’s beautiful about German culture. The group recorded the Brandenburg Concertos in 1935, which became a global best-seller introducing Bach’s concertos to the world.

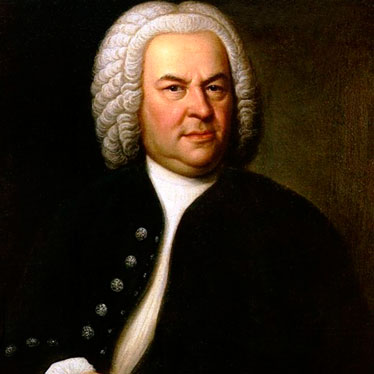

Johann Sebastian Bach in a portrait by Elias Gottlob Haussmann, courtesy of wikimedia.org

This article sponsored by Thomastik-Infeld